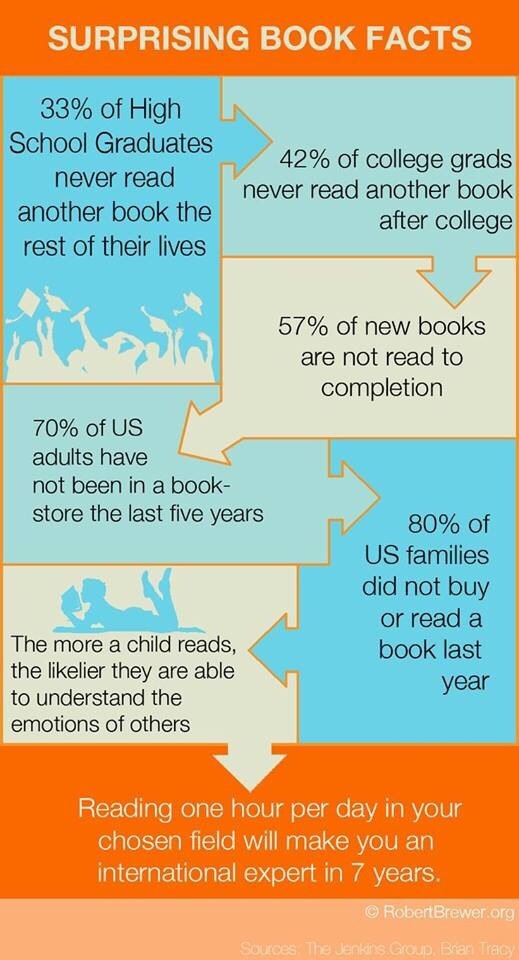

For those who think that all of those fourth graders not reading at grade level will just catch up and that we don’t need to worry about ensuring all our elementary schools are using evidence-based literacy instruction, try considering some of these stats …

Workforce

The Most Useless College Majors

We used to joke about those who took classes like “children’s games,” “rocks for jocks,” or even “underwater basket weaving” while in college. That was then, when college degrees guaranteed gainful employment. This is now, when a liberal arts degree guarantees very little.

Jobs and Ed, Ed and Jobs

One has to be living under a rock not to recognize that that education and jobs share a strong bond. As we look for ways to rebuild our economy and create new jobs, it is clear that reforming our K-12 education systems, ensuring all students have access to the knowledge and skills necessary to perform in our future economy, is a non-negotiable.

It’s shameful that we can’t fill open jobs in an economy like this. And it is deplorable that one’s ability to get a strong public education depends, in large part, on race, family income, or zip code. We have no excuse for not preparing our kids, all of our kids, to meet the demands of a 21st century economy. Education is an economic development strategy – the best one that’s out there. We should be redoubling our efforts to ensure that policy makers see economic development and education as two sides of the same coin, and look to them to guide states, localities, and the nation toward meaningful reforms that will prepare all of our kids for college, career, and a productive life.

Reconnecting McDowell County, WV

Readers of Eduflack know I often speak of my roots and connections to West Virginia. I am a proud graduate of Jefferson County High School in Shenandoah Junction, WV (Go, Cougars!) But I am particularly privileged to have served on the staff of one of the greatest U.S. Senators in our nation’s history, the Honorable Robert C. Byrd.

We understand that there are no simple solutions — no easy answers or quick fixes. Together, we are striving to meet these challenges, but we know we won’t accomplish that in a day, a month, or even a year. We will find ways to measure our progress, and we believe that the changes we propose and implement must be judged by rigorous standards of accountability. We accept that this will be a long-term endeavor, and we commit to stay engaged until we have achieved our goals of building the support systems the students need and helping the residents of McDowell County to take charge of their desire for a better life ahead.

National Skill Standards, Again??

A Work-Around for Edu-Jobs?

Edu-jobs. For the past month or so, we have been hearing how our K-12 public school systems need $23 billion in emergency funding from the federal government in order to keep teachers across the nation in jobs this fall. EdSec Arne Duncan has made passioned pleas on Capitol Hill for such funding. The teachers unions have stood behind Duncan’s request in a way far stronger than they have ever supported the EdSec. And House leaders like Education and Labor Committee Chairman George Miller (CA) and Appropriations Chairman David Obey (WI) have echoed the calls and urged their fellow leaders on the Hill to ask, “what about the teachers?”

To date, though, Congress has resisted. Many senators, wary of spending more and more money, have refused to move the issue forward. They even cite the absence of edu-jobs from President Obama’s request for emergency funding from Congress. Despite the best of intentions, right now, it seems like efforts to fund edu-jobs aren’t going anywhere.

It all has Eduflack thinking. In February of 2009, the U.S. Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a $787 billion spending bill designed to help states and localities IMMEDIATELY deal with the budget shortfalls and shrinking coffers just about everyone was facing. By spring, we saw roadside signs erected declaring that this public works project or these jobs were funded courtesy of ARRA. Our K-12 schools got a big chunk of that money as well, with ARRA funding Race to the Top, i3, and big boosts to Title I and IDEA funding just for starters.

We’ve also heard how a great deal of the education ARRA funds went back to the school districts to pay for salaries. Despite the initial guidance that stimulus dollars were meant to be one-time injections, and were not designed to pay for long-term obligations (like teachers’ salaries) that would have to be funded well after all the ARRA money was spent, we still used the stimulus for teachers’ salaries. Just last month, one of President Obama’s leading economic advisors declared ARRA had saved 400,000 educator jobs across the country (while saying that one out of every 15 teachers could now be laid off without the additional $23 billion).

Curiosity has gotten the better of Eduflack. We committed $787 billion to economic stimulus that was needed as soon as possible. The funds were made available in February of 2009. It is now June 2010. The nearly $800 billion is all supposed to be spent by September of this year. According to the Recovery website, of that $787 billion that was so desperately needed, $406 billion has actually been paid out. There is still $381 billion still sitting in the kitty.

In California, the state seen as having the most dire current economic position (and the most difficulty paying teachers), only $8.8 billion of the nearly $22 billion promised to the Golden State has been dispersed. In New York, they’ve gotten $2.5 billion of their $12 billion. Illinois has taken in $3.7 billion of its $8.1 billion. Georgia’s taken in $2 billion of its $5.4 billion. Oregon’s taken in just $809 million of its $2.5 billion. And even the cash-strapped Ohio has only tapped $1.7 billion of its available $7.6 billion.

So it begs the question, why don’t we just reallocate some of the committed $787 billion in stimulus money to pay for the $23 billion in edu-jobs? The money was designed to help states and localities save jobs. Check. Funds have already been used to save teachers’ jobs (those 400K that Christina Romer touts). Check. There is plenty of money that still hasn’t been spent. Check. And we need to spend this soon. Seems like a win-win for all involved. And one could even win over the reformer crowd (which has been concerned that edu-jobs funding will simply perpetuate the notion of last hired, first fired and prize tenure over effective teaching). Tie the dollars to the priorities in ARRA, using RttT language to ensure that new edu-jobs spending is aligned with teacher and principal quality provisions being moved through Race.

A simplistic idea? Perhaps. But new federal funding for teachers’ jobs isn’t going anywhere. If the goal is to protect those educators and avoid laying off the “one in 15,” then why not ask Congress to reallocate the funding they’ve already spent? At this point, it is just like asking if we can use our allowance to buy baseball cards instead of bubble gum. The money’s already left Congress’ wallet.

A College Degree for Every Child?

By now, most in national education policy circles realize we are transitioning from the era of AYP to the era of college/career ready. Instead of using middle school reading and math proficiency as our yardstick, we will soon be using the college- and career-ready common core standards to determine if states, districts, and schools are truly making progress toward student achievement.

Over at National Journal’s Education Experts Blog, they’ve been spending the week discussing EdSec Arne Duncan’s Blueprint for ESEA Reauthorization. Lots of interesting opinion here, from Sandy Kress’ significant disappointment to Michael Lomax’ support to real concerns about the “5 percent rule” to a general feeling that lack of details is a good thing in planning legislative policy.

But this morning, your NJ ring leader Eliza Kligman broke a bit from protocol and posted an anonymous comment from a reader in South Carolina. (For those who don’t realize the participant list for the Education Experts Blog is a virtual who’s who. There are MANY in the chattering class who desperately want to be added to the list, but haven’t yet. And to focus on these experts, National Journal doesn’t allow readers to post comments to the blog. A general concept that usually means the kiss of death for a blog, but seems to work for National Journal.)

But I digress. This reader raised an important question with regard to the next generation of ESEA and our intent of getting every child in the United States “college ready.” In fact, the comment is a little more pointed, with the reader stating, “if everyone is highly technically trained or college educated who is going to check out my groceries, cut down the dead tree in my back yard, tow my car when it breaks down, or take my money when I buy gas at the convenience store? If you think the illegal alien problem is bad now, just wait until all of us middle class soon-to-be-elderly are told we have to pay highly skilled wages tot he guy who cuts our grass.”

While SC is mixing and matching a wide range of policy issues that shouldn’t be joined together (such as who is worthy of earning highly skilled wages and the immigration issue), he does start to touch on an interesting point. But Eduflack would ask a more important question — does being college ready mean that every student should actually attend college?

In today’s global economy, just about everyone who holds a full-time job likely needs the sort of knowledge and skills that would be deemed “college- and career-ready.” That guy fixing his car is most likely ASE certified and needs to be well versed in computers, math, and other subjects to successfully repair what are now four-wheeled computers with AC and a killer sound system. The guy cutting the tree now needs to know ecology and life sciences and hopefully some math to generate accurate invoices. And regardless of the job, we want everyone to be literate with some level of social skill. So the fear expressed by SC and many, many others is a bit of a straw man.

It opens the larger question, though. As a nation, though, we have set a national goal to have the highest percentage of college graduates in the world by the year 2020. Why? Is it more important for someone to hold a diploma or a good-paying job? What is the measure of a successful nation? A strong economy? A robust workforce? Or the total worth of outstanding student loans?

I don’t mean to be negative here, but Eduflack has long believed we are selling students a bill of goods by telling them everyone should go to college. First off, when we say college, most mean four-year degrees (and that’s even how that national goal is being measured). But what about the knowledge and skills that are earned through community college programs and career and technical education programs? What about military service, where four years of Army training may be far more beneficial than a BA in the liberal arts? What about those whose passion is pursuing a trade, or the true entrepreneurs who are itching to open a business and pursue their passion? Are all of those pursuits worth less because they don’t come attached to a four-year degree?

When Eduflack got into this discussion a few years ago, it generated an ongoing offline debate with a liberal arts professor from a college in the Pacific Northwest. He regularly called me a complete idiot, saying I completely missed the point. The role of college, he would say, is not to prepare kids for career, it was to broaden their minds and open them up to new experiences.

The ESEA Blueprint is correct is seeking to ensure that all those who graduate from U.S. high schools are ready for either college or career. But we need to have a much deeper discussion of who should go to college, why they should pursue postsecondary education, and what the expected return on investment is for such a pursuit. In an era where an aspiring college student can drop more than $200,000 to earn a BA from a private liberal arts institution, ROI becomes an important topic — for lenders, potential employers, and the students themselves.

How the ARRA Times Change

Just a few short months ago, educators with brimming with enthusiasm about the potential economic stimulus funding would offer. We talked about those new programs that could be pursued. We discussed how existing efforts could be broadened and expanded. We dreamed about the possibilities of doing using the “startup” money found in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to do new things designed to spark innovation in the classroom and long-term academic improvement in the student.

Thank you for your interest in funding available to Virginia through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). Both transparency and accountability are core requirements of ARRA-and I am pleased to update you on the Commonwealth’s progress on projects and proposals related to the Recovery Act.

As you may know, my administration launched stimulus.virginia.gov earlier this year to gather project ideas from individuals, groups, and localities for potential funding through ARRA. Between February 10 and the March 6 submission deadline, more than 9,100 project proposals totaling $465.6 billion were suggested through the website. Since then, these proposals have been sorted and sent to the appropriate Cabinet Secretariat for evaluation.

Virginia‘s General Assembly incorporated ARRA program funding that is administered by agencies into the state budget and directed it to specific activities. The Recovery Act alsoincreased funding to existing federal programs rather than allowing states to fund projects from a large discretionary fund. As a result, what little discretionary ARRA funding that existed was used by the General Assembly to address Virginia‘s projected budget shortfall. While these decisions around ARRA and the state budget-which I signed into law on March 30-are continuing to ease the economic downturn in the Commonwealth, they also mean there is no discretionary funding available to dedicate to specific projects.

Currently, under each Cabinet Secretariat

, state agencies are working with their federal counterparts to implement ARRA funding for programs ranging from education to water quality, totransportation, to energy. These programs require that all project ideas meet specific criteria and be formally submitted through traditional federal funding processes. In most cases, these processes are now complete and work is ready to begin. Most of the projects that were funded via traditional federal measures were submitted as a project idea.

Although there are many other project ideas that could contribute to our economic recovery, a number of proposals we’ve received-including private business investment and tax reduction-fall outside the scope of ARRA funding provided to the Commonwealth.

I strongly encourage you to monitor the stimulus.virginia.gov website for information on projects being funded by the ARRA and to explore potential opportunities through the competitive grants process. Some projects submitted through stimulus.virginia.gov not selected for ARRA funds may be eligible to apply for a competitive grant directly from a federal agency.

Thank you again for your input. I always appreciate hearing from citizens of the Commonwealth and will take your thoughts and proposals into consideration as we work to get our economy back on track through ARRA. Please do not hesitate to contact me via my web form, and find out more about my initiatives on my web site at www.governor.virginia.gov.

Sincerely,

Timothy M. Kaine

Governo

r of the Commonwealth of Virginia

Changing the Game on College Funding

We have all heard the stories (and jokes) about college students who are on the five-, six-, or even seven-year plan. Those students who love their college years so much, that they simply never want to leave those glory days. Some maximize the financial aid packages available to them, some have generous families, and others just find a way to stick around their hopeful alma mater.

Presidential Commencement in the Desert

In recent weeks, there has been a great deal of discussion and debate about President Obama’s decision to speak at graduation festivities at the University of Notre Dame. But little had been said about yesterday’s presidential commencement address at Arizona State University. Yes, there was some initial discussion about ASU’s decision not to award Obama the traditional honorary degree (apparently, ASU’s policy is that one is recognized for their full lifetime body of work, and the President of the United States still has to prove himself and still has other career chapters ahead of him), but that’s been about it. But few are discussing what’s behind the curtain on last night’s address in Tempe.

na State, you just get the spotlight because you won the White House lottery this year. Next year, such concerns can be raised about future institutions. But when you get the President speaking about hope and opportunity for your graduates, one has to take a close took at those who failed to don the cap and gown, why they weren’t in the stadium last evening, and what that means for ASU, Arizona, and the nation.